Perhaps the best way to introduce Shane Granger is to quote from the flyleaf of…

Features

Cruising Australia’s east coast: ‘A delicious mix of modern convenience and truly isolated’ adventure

When we tell people we’re bluewater cruising around the world, the first question is almost…

Great seamanship: Chasing the Dawn

The title of Nick Moloney’s remarkable book about breaking the Jules Verne unlimited round the…

10 women doing great things in competitive sailing right now

With a Women’s America’s Cup due to start in 2024, a gender balanced sailing event…

Great seamanship: Fifty South to Fifty South

The German pilot schooner Elbe 5, built in 1883, has had a remarkable life. A…

Don McIntyre the adventurer who launched retro-round the world racing

Don McIntyre is on relaxed form when he calls from Les Sables d’Olonne. His current…

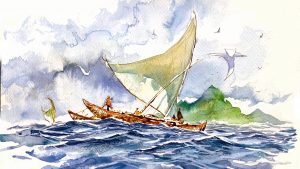

James Wharram: life and legacy of the iconic designer

Falmouth, Cornwall, 1955: a legend is born along Customs House Quay. A smartly dressed young…

What’s it like to sail to the most remote of the South Sandwich Islands?

We dropped anchor in 12m of water, a long stone’s throw from an unfriendly rocky…

Gallery: Eleonora – an owner’s story

This article on owning the remarkable 162ft schooner Eleonara is from the archives. It started…

Columbia: a completely reinvented stunning classic yacht

What particularly strikes you as you step on board Columbia is the atmosphere. Judging from…

J Class: the enduring appeal of the world’s most majestic yachts

One of the most awe-inspiring sights in modern yachting is the Spirit of Tradition fleet…

Great seamanship: inside a volcanic caldera in 50-knot winds

Joe Phelan is one of Ireland’s great sailors. With his wife and equal partner Trish…

The land of four kings: discovering Indonesia by yacht

The night is almost over when we motor our dinghy across Namatote Strait, drawn by…

Great seamanship: The Lugworm Chronicles

For anyone interested in small-boat voyaging – or indeed, any sailor wanting to get seriously…

Great seamanship: The Voyage of the Aegre

Back in July 1973, Nicholas Grainger and his wife, Julie, sailed from north-west Scotland bound…

Best sailing films on Netflix, Prime and more

Recent years have seen a proliferation of sailing films arriving on streaming platforms, with Netflix…

Round the Island Race 2023: How to prepare for victory

The exact nature of the error that led someone to share the wisdom of the…

15,000 miles around Europe’s far north in a windsurfer camping under a sail – a fascinating tale

Most of my deepwater sailing I’ve done in conventional yachts or classics. Board sailing and…

Adrift in the Pacific: One sailor’s incredible story of survival

Staring down from the cockpit into the cabin of my vintage sloop I tried to…

The new wingsail concept that could revolutionise shipping

The words ‘muscles’ and ‘sails’ are often included in the same sentence, such is the…